In 1900, when a young man from Virginia first arrived in Schenectady, he was fascinated by the General Electric Company and with all the opportunities it offered. Having worked for several years as a surveyor and a foreman for a railroad, he soon was accepted into the “on test” engineering training program, and by 1904 was assigned to the Power and Mining Engineering Department. His enthusiasm for the out-of-doors led him to become a sort of pied piper around Schenectady, taking his friends on excursions throughout the region and sparking their interests in the pursuit of exotic sports. Gradually, and perhaps inevitably, this led many of these “happy campers” to become enthusiastic about protecting the mountains, lakes, and islands they loved, and to become zealots for the cause of preservation. Many of them became active in the political process and in conducting effective political campaigns.

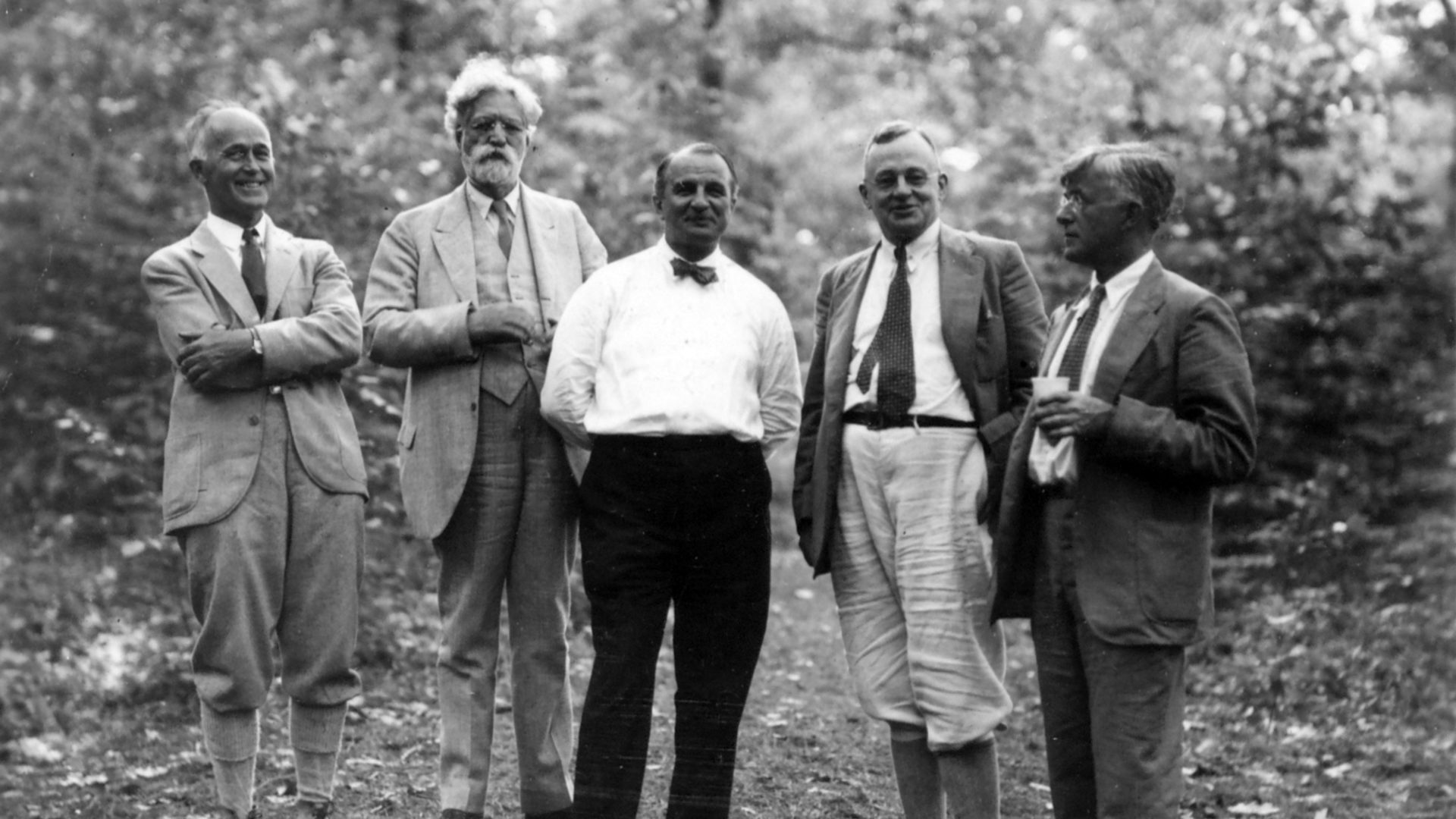

Although he never ran for political office himself, Apperson earned the respect of some of the top politicians of his day, including Al Smith and Franklin D. Roosevelt, and learned about the legal battles being waged in Albany over the laws governing the forest preserve lands. He became the leader of a grassroots effort to educate the people of New York about the importance of wild places, both as a way to protect the water sources but also to ensure that there would still be undeveloped natural areas. Few scholars have had a chance to dig into the Apperson archives and find out how Apperson managed to launch his “Schenectady Force” (as Frank Graham. in The Adirondack Park: A Political History, described it), capable of influencing public opinion and getting out the vote in critical elections.

He spent more than five decades advocating for the “forever wild” clause of the constitution, all while working full time at G.E, for 47 years, and while continuing his efforts to protect the islands at Lake George. He purchased Dome Island in 1939, to prevent the owner from developing a hotel or other structures, and in 1956, he decided to donate the island to the Nature Conservancy, as one of its first nature preserves. After his death, in 1963, his friends worked for many years, organizing his papers and photographs, and eventually leaving his archives in the care of the Adirondack Research Library, now housed in the Kelly Adirondack Center (Union College). Along with the papers left by Paul Schaefer, Apperson’s protégé, the collection has become a valuable educational resource capable of serving students and other researchers for generations to come.

Search the the Apperson Archives for more about John S. Apperson