Throughout the first half of the 20th century, activists played an important role in protecting and preserving New York’s most famous lake and tourist attraction – Lake George.

It all started when a group of friends, mainly employees at General Electric in Schenectady, began camping on the islands in the Narrows, and introducing various forms of recreation. They noticed that the islands were losing top soil, washed away during extended periods of high water, and wondered about the laws governing the operations of the dam at the northern outlet of the lake. Should a lumber mill (International Paper Company) be allowed to flood the islands and shores, using the lake as if it were a mill pond?

This is their story…

Lake George is without comparison, the most beautiful water I ever saw; formed by a contour of mountains into a basin… finely interspersed with islands, its water limpid as crystal, and the mountain sides covered with rich groves… down to the water-edge: here and there precipices of rock to checker the scene and save it from monotony.

– Thomas Jefferson, May 31, 1791

Lake George:

A 20th Century Battleground

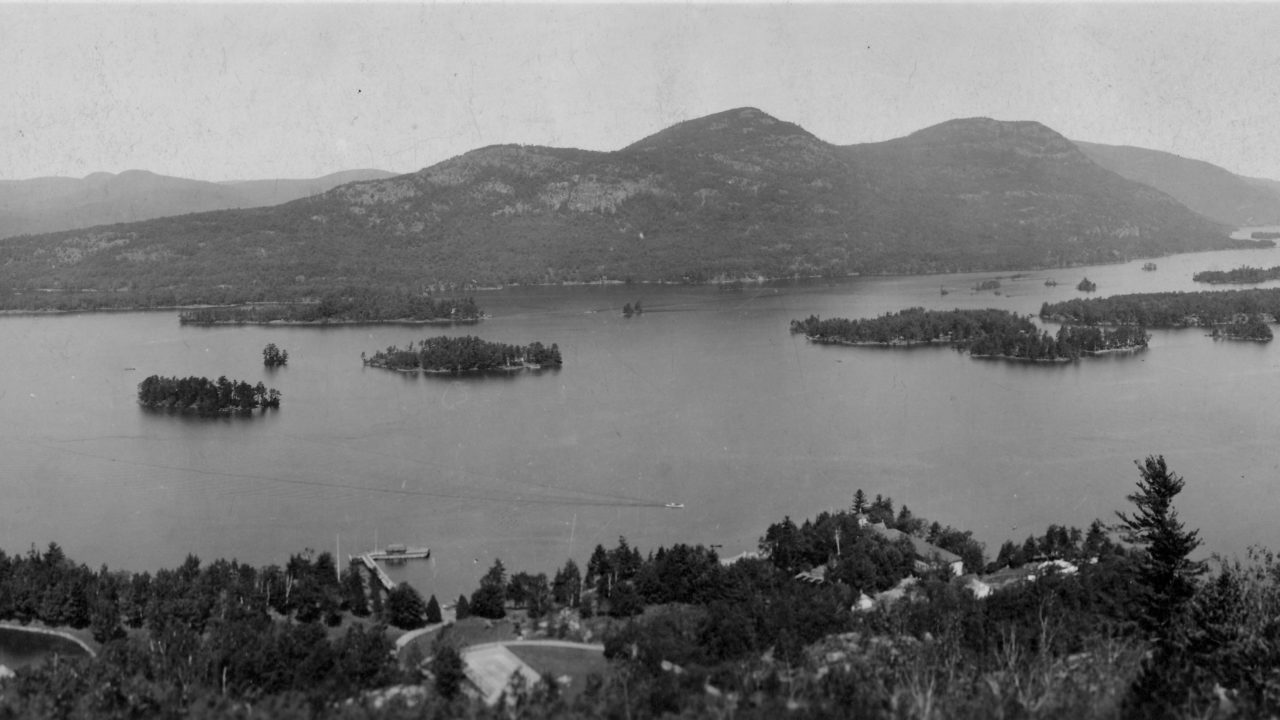

By 1900, Lake George had become one of New York’s major tourist destinations, but the famous scenery was threatened by commercial development. Fortunately, a group of activists, led by a young man from Virginia – John Apperson – took action. Apperson, an engineer working for the General Electric Company in Schenectady, and his team decided to try and protect the beautiful islands and shores from harm.

A broad coalition of philanthropists, politicians, clubs and organizations were enlisted to help protect Lake George, as evidenced by this coed rock-hauling party, c. 1913.

Rip-rapping the shores of islands – From 1908 – 1918, Apperson personally supervised the construction of protective rock walls of state-owned islands at Lake George. He recruited over three hundred friends to help haul rocks and build walls, using a process he called rip-rapping.

One thing led to another, so that by 1915, he had been elected a delegate to the constitutional convention and gave a speech defending the protections of “forever wild.” In 1917, the State allocated $10,000 to hire workers to expand this project, eventually protecting fifty islands.

Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.

– John Muir

John Muir and the Sierra Club

In 1913, when the U.S. Congress voted to allow the City of San Francisco to build a hydroelectric dam and reservoir in the Hetch Hetchy Valley, in Yosemite National Park, preservationists across the nation were alarmed and disappointed.

This defeat came despite a vigorous and protracted battle waged by John Muir and his Sierra Club, an early example of grassroots lobbying. John Apperson and his activist friends were paying close attention to this national debate, and found a similar cause at Lake George.

That same year, 1913, Apperson started seeking advice from legal experts to find out how to prevent a paper mill from destroying the trees on state owned islands, and causing entire islands to disappear. His legal challenge remains a relatively obscure chapter in New York’s Adirondack history – and few people realize how many islands he saved.

The International Paper Company

The International Paper Company constructed a dam at Ticonderoga in 1903, replacing a natural dam that had been operating effectively for a century or more. They also added 8 inch flash boards above the dam, resulting in higher water levels at Lake George – of up to four feet.

In 1908, property owners at Lake George began to complain about the damage caused by the higher water levels, and asked the Lake George Association to investigate.

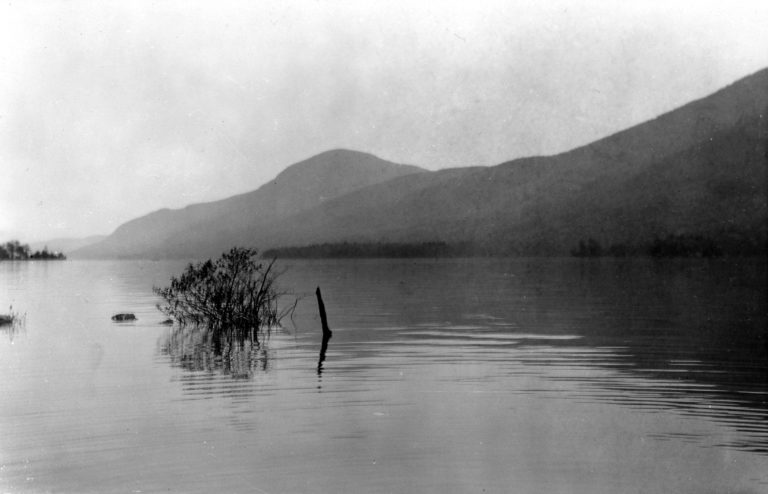

In this scene, showing an island under water, he hoped to alert the public to the damage being done by the high water levels caused by the flash boards at the International Paper Company’s dam at Ticonderoga.

In 1909, Apperson purchased an Auto-Graphex camera, and began pursuing photography as a hobby, first on glass plates and later on film. Eventually he found a practical use for these images, publishing many of them in pamphlets as a way to educate the public about the problems he found.

The Conservation Commissioner, George Van Kennan, responded in a letter explaining that the industry had acted responsibly, and that there was no need to take action. That response apparently seemed satisfactory to the LGA, but not to Apperson and his friends – who were very concerned about damage being done to state islands.

For the “Great and Gracious,” who owned estates on Millionaire’s Row, Lake George was an exclusive playground. Like the Lake Placid Club, where Jews and consumptives were barred from membership, the Lake George Club and the Lake George Association had strict membership requirements. Most of these club members were not particularly concerned about preserving the natural, undeveloped scenery for generations to follow.

However, a few far-sighted philanthropists, such as George Foster Peabody, William K. Bixby, and Mrs. Stephen (Mary) Loines, took a more progressive view. They shared a bold vision, along with John Apperson and his friends, of a Lake George Park, to be accessible to all citizens of the state.

Dream of a Lake George Park

In 1923, when Mary Loines offered to donate 15 acres of her farm land in Northwest Bay to the state (as the first step toward protecting Tongue Mountain), a controversy erupted. At a meeting of the LGA, people expressed anger about the Loines family gift, and about the general idea of a Lake George Park.

Also that year, Governor Al Smith and Robert Moses, Secretary for the New York Parks Association, were offered a boat ride into the Narrows – to see the site for a proposed highway to-be constructed around the rim of Tongue Mountain.

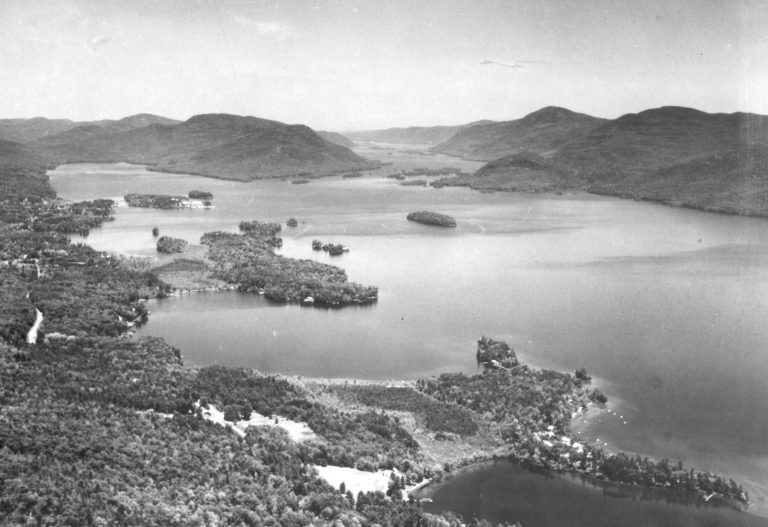

Apperson took Gov. Smith on a boat ride from Bolton, out past Dome Island, and then north to have a look at Tongue Mountain and the Narrows.

Apperson, who had planned the excursion, pointed out how construction of such a road along the steep shoreline would be enormously expensive, and totally disfigure the scenic view. Gov. Smith agreed with Apperson, and Robert Moses was forced to change his plans.

First step in forming a Lake George Park – bringing Tongue Mountain under state ownership.

Apperson considered logging one of the most serious commercial threats to the beautiful scenery, but it would take many years to find an effective remedy. One way to block logging companies from cutting trees on Tongue Mountain or Black Mountain was to purchase shoreline property – and block the logging roads from getting access to the lake.

He bought a camp on Tongue Mountain in 1918, expressly for that purpose. He pushed and prodded state officials to purchase all of Tongue Mountain, and to bring it under the protection of forever wild – using the $75,000 set aside by the legislature. But Robert Moses and top state officials procrastinated and dallied, while land prices continued to soar.

Dome Island

Apperson had a special interest in this island, and understood how vulnerable it was to damage from wind, erosion, and human occupation. He adopted it and repaired the shores – even when it was still privately owned.

Then in 1939, he somehow found the money to purchase the island ($4,500), to prevent the owners from cutting trees and constructing a hotel. It took him another 18 years to find a long-term solution – eventually donating it to the newly formed Eastern NY Chapter of the Nature Conservancy, in 1956.

The critical factor in this transaction was the creation of a special Dome Island Fund – a sort of endowment to protect the island in perpetuity. His friends raised $20,000!

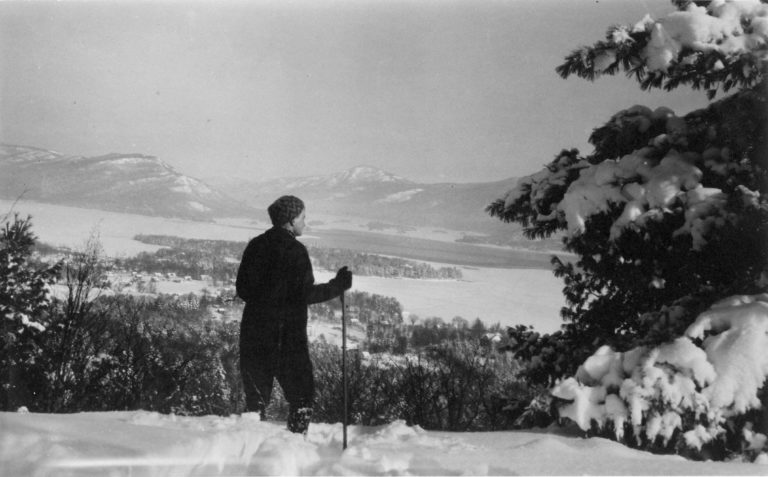

He made a joint purchase of land in Huddle Bay (the old Lake View Hotel) with G. Hall Roosevelt (Eleanor’s brother) and William Dalton, in 1920. This became his “Main Camp” and base of operations. In 1921. they hosted a regatta for the American Canoe Association. And here, in 1925, Apperson promoted a form of cross country skiing.

From Barber Mountain, a.k.a. Appy Top, on skis (with Lake George in the background). Apperson perfected a technique of skiing up steep hills by simply wrapping raw-hide around his skis – thus providing enough traction to allow him to climb.

The Schenectady Force

By 1930, Apperson had built a grass-roots organization known as the Schenectady Force – capable of fighting, and winning, many legislative battles. The next step, in order to be truly effective, was to enlist the help of several philanthropists, politicians, and other well-known individuals, to form a non-profit organization – the Forest Preserve Association of New York (1934). Apperson became the C.E.O. (unpaid), and other key members (George Foster Peabody, Senator Ellwood Rabenold, Dr. E. McDonald Stanton, and Dr. Irving Langmuir) provided money and influence.

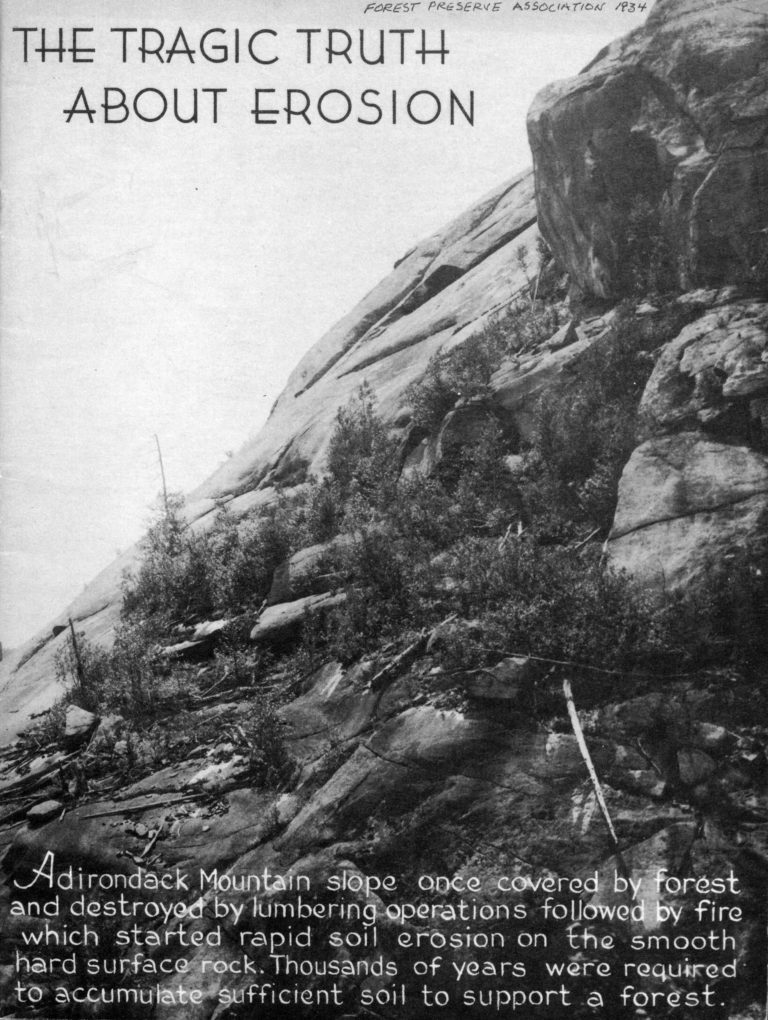

In 1934, during the dust bowl, Apperson and his new organization, the Forest Preserve Association of New York, provided the funding necessary for the U. S. Soil Conservation Service (in Washington, DC) to publish an educational pamphlet about agricultural practices that were causing erosion. 40,000 copies of the pamphlet, entitled The Tragic Truth About Erosion, were distributed to extension offices in every state.

Featured on the cover of the pamphlet was this dramatic image, one of Apperson’s documentary photos from the Adirondack mountains.

Lake George Today

John Apperson, a life-long champion for Lake George, must have worried about who would carry on after his death. Many of his projects can be seen and admired, such as Dome Island, and the islands in the Narrows, Tongue Mountain, and Black Mountain. They are protected by a conservation organization (The Nature Conservancy) or the State of New York.

Modern day threats, however, extend to larger environmental and governmental issues, such as acid rain, invasive species, and legal battles over riparian rights, land prices, taxes, and the on-going pressure to weaken the protections of “forever wild”.

Fortunately, many organizations have taken up the call to action, including The Fund for Lake George, the Darrin Fresh Water Institute (educating the public about how to maintain water quality), and the Lake George Land Conservancy (setting aside watershed properties as nature preserves).

We hope this website, and the information published here about specific battles and strategies, will help recruit more “ordinary people” to the cause.